Fort Picklecombe ~ Rame Peninsular, South East Cornwall.

Client : Private.

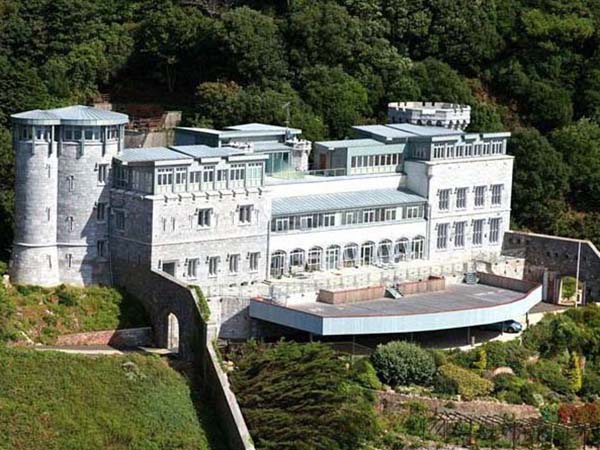

Fort Picklecombe is situated on the extreme South Eastern coast of Cornwall, a few miles away from the nearby city of Plymouth in the neighbouring county of Devon.

Since the 1970’s the fort has been a residential complex but it has a long history dating back 150 years.

Fort Picklecombe is part of a chain of defensive forts constructed around the coast of Britain during the Victorian period. The Prime Minister of the day was Lord Palmerston and he commissioned these fortifications after concerns about the French Navy and the possibility of a large scale invasion from across the sea. After a detailed report from the Commissioners it was concluded that just over £3,000,000 would be set aside to fortify the Plymouth area alone in order to protect the Naval base at Devonport. Out of a total budget of almost £12,000,000 for all the fortifications around the British coastline, Plymouth had the lions share. There had been a defensive ‘battery’ here since 1800 and this had been rebuilt in 1860. Palmerston’s granite faced fort we see today was built between 1864 and 1871. At that time Palmerston was heavily criticized for having these fortifications constructed. By the time they had been completed the threat of war had passed and also with the advancement of gun technology these fortifications became out-dated and obsolete making them the most costly fixed defence scheme in peacetime Britain. As a consequence these fortifications became known as ‘The Palmerston’s Follies’. A ‘folly’ is a costly ornamented building or structure with no practical value.

Perched up high in an elevated position behind the main fort complex is a grand building called the Officer’s Mess and this was built in 1848. Both fort and Officers’ Mess are Grade II listed.

When the Officer’s Mess was constructed the landowner, who was the Earl of Mount Edgecombe, insisted that the architecture emulated that of Warwick Castle and was to include towers, turrets, arrow-slits and castellations.

Being one of the most famous castles in the world Warwick Castle was first built as a fortress with a central ‘keep’ which had successive lines of fortifications and towers added over hundreds of years during several reigns. It was constructed during the Medieval ages replacing an original wooden ‘Motte-and-Bailey’ castle which had been built by William the Conqueror in 1068 A.D. Re-built in stone during the 12th century, its defences were significantly re-fortified between 1330 and 1360 by Thomas De Beauchamp, the 11th Earl of Warwick, with a gatehouse and ‘barbican’ which is a fortified entrance, and had two towers built either side of it. The first of the towers to be built was Caesar’s tower followed by the later addition named Guy’s tower and both are styled on the ‘French Donjon’ (dungeon) or ‘Great Tower’. This castle is one of the most recognised examples of 14th century military architecture.

Having been modelled on the same lines as that at Warwick Castle, the Officer’s Mess at Fort Picklecombe has some great architectural features. It too has a tower named Guy’s tower. Being the main defensive system for any fortification and because of their height and position above and out from the main walls of the fortification, towers give a clear view to target the enemy below.

Its corbelled parapet has ‘machicolations’. Machicolations are holes in the floor between the corbels supporting the battlement. They were used in Medieval times to drop stones from them or pour boiling oil onto the enemy below. In later periods this feature was used for decorative purposes.

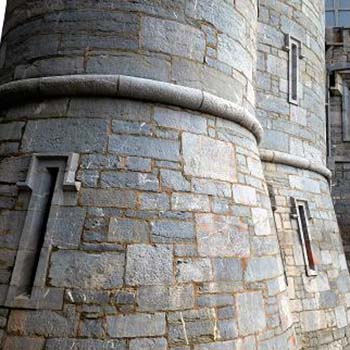

The base of this octagonal tower is ‘battered’ from ground level up to the string course which means it is constructed at an angle and not upright. The ‘quoin’ stones along with some of the stonework have chevrons cut into them. The chevrons were most likely cut into the stone after it was built.

It has a few small ‘crenellated’ turrets positioned along the curtain walling.

Along with a ‘bartizan’.

A ‘bartizan’ is an overhanging wall mounted turret sat on a projecting corbel, usually found on a corner of a castle or fortification. It is also known as a ‘guerite’ or an ‘echauguette’. They were used to protect the person inside whilst they were looking out at the surrounding area. These usually had ‘arrow-slit’ windows incorporated into its construction.

Many of the windows on the Officer’s Mess are designed as ‘arrow-slits’.

All of the windows have a ‘label’ or ‘hood’ mould over the top of them. This projected detail is designed to throw rainwater away from window or door openings. A hood mould is usually terminated at the side of the opening and this is called a ‘hood stop’. In architecture the hood mould was introduced during the ‘Romanesque’ period between the 6th and 10th centuries and then later developed into the Gothic style in the 12th century. The architecture on the Officer’s Mess is in the style of ‘Tudor Gothic’.

It also has a second tower, and like its counterpart based on the designs at Warwick Castle, this too is called Caesar’s tower. It’s actually three towers in one and on plan would resemble a ‘clover-leaf’. This shape is described as a ‘trilobed’ meaning it has three lobes.

The base of these three interlocking towers are also ‘battered’ from ground level up to the string course.

It was on the base of this tower that we were asked to take a look at an unusual job on one of the ‘arrowslit’ windows. The client required this window opening to be altered and become a fire escape window known as a ‘fire egress’. To comply with building regulations this meant that the new opening had to be a minimum of 700mm high and the width also had to be 700mm. As the Officer’s Mess is Grade II listed, listed planning consent had to be submitted to the local council for approval. The conservation officer insisted that the position of ‘hood’ mould remained untouched. The sill at the bottom of the opening had to be re-used along with all of the ‘quoin’ stones that were removed to accommodate the new opening. Any new stone required had to match the original stone that was used in its construction and also a natural hydraulic lime mortar used to build the new opening.

Before any work could proceed we had to source a supply of stone. The stonework on the Officer’s mess consists of Plymouth limestone and would of originally came from the Bedford quarries at Plymstock in Plymouth. This quarry once supplied millions of tons of stone to build the Breakwater in Plymouth Sound during the 1800’s. This quarry had ceased the production of limestone many years ago so we had to source some Plymouth limestone from a reclamation yard. When we had suitable blocks of stone it then had to be approved by the conservation officer and once this was approved we were good to carry on with the work.

Any stone removed to form the new opening had to be re-used so we had to be careful not to damage any. This was achieved by ‘stitch’ drilling the joints with an electric drill equipped with a small tungsten tipped bit. The mortar joint is constantly drilled around the stone until all the mortar has been completely removed.

Having assessed our plan of attack, the first stone we cut out was the ‘quoin’ directly beneath the ‘hood’ mould. Wooden wedges are placed in the bed joint as this supports the stone whilst drilling is taking place and it also protects the edges when the stone finally breaks free.

Once free the stone is then set aside for re-use.

The first stone is always the most trickiest to remove, but after it has been removed, the ‘quoins’ below are much easier to take out as there is more room to work around them.

A prop is placed under the ‘hood’ mould to prevent any potential movement.

The same process is carried out to the opposite side and then the sill is removed. Measurements for the opening are then calculated to determine the new position of the sill.

More stonework is cut out at a lower position to accommodate the sill and then it is set into place.

After the sill is in place, the existing ‘quoin’ stones that were set aside for re-use are measured and their new positions are marked and cut out with a water fed diamond cutter. At this stage we have only cut back into the tower wall to a depth of about 300mm. This gives enough room to set in the ‘quoin’ stones so we can build up to the ‘hood’ mould and make sure that it doesn’t move once the new external stonework has been completed. The inside stonework will stay in place until the external stonework is finished as this gives extra structural support internally.

In the meantime the blocks of reclaimed Plymouth limestone were cut down and prepared into their modular sizes ready for shaping and re-dressing on site.

Because the new opening was much wider than the original ‘arrow-slit’ window which actually protruded out from the face of the tower walls by about 25mm, we had to cut and dress new sill sections in limestone that had to match up to the position of the original sill across to the new positions of the original ‘quoin’ stones which were going to be set back in. Not only did these new sections have to protrude from the face of the tower wall, they also had to be shaped to suit the radius of the tower as well as the ‘battered’ angle to which the base of the tower leaned. These new sill sections were basically an extension to the original sill. It is better to do this shaping on site as all the correct angles can be determined as work proceeds. We had to cut and dress four of these sections, two for the bottom of the opening and a further two ‘window heads’ for the top to meet up with the ‘hood’ mould.

When these were prepared they were set into place.

Then the existing ‘quoins’ and adjacent stonework could be set into their positions.

When both sides had been built up, the window head returns were set in to pick up the original ‘hood’ mould which completed the size of the new opening and made sure everything wasn’t going to move.

That then enabled us break all the way through the tower wall to the inside. These walls are over four feet thick at sill level. They are solid and were designed to keep out the French, but they won’t stop a stonemason with the correct tools!

When we had broken through and got everything prepared we proceeded to build up the side reveals. These reveals were also built from new limestone and they had to be shaped and dressed on site to suit. We then set in concrete lintels and built brickwork above them to pick up the top of the opening. These lintels were set slightly higher than the window head so they could be clad with timber and painted.

After all this was finished the final bit of stonework to complete was behind the sill. Again new limestone was shaped and dressed to fit and all the joints for the stonework to the new opening were pointed using a natural hydraulic lime mortar.

The ‘arrow-slit’ window is also known as an ‘arrow-loop’, a ‘loop-hole’ and sometimes a ‘balistraria’ to name a few, and their names are determined by its design and what sort of weapon is being fired from them. These thin vertical apertures are often cut away on the inside at an oblique angle to give the archer a wide field of view to fire weapons whilst giving him greater protection from the enemy since they have a smaller target to aim at. With the advancement of cannon and gun technology these openings became known as ‘gun-loops’. Archimedes is credited with the invention of the ‘arrow-slit’ window during the siege of Syracuse 214-212 B.C.