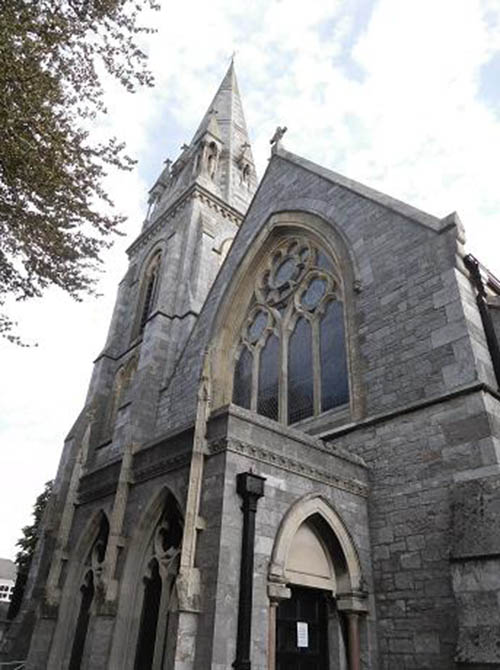

St. Jude’s Church ~ Plymouth, Devon.

Client : St. Jude’s Church.

St. Jude’s Church is the daughter church of Charles Church in Plymouth and it owes its existence to two wealthy families who lived just a few yards from the present church itself. One was the Bewes family from Beaumont House and the other being the Culme-Seymour family from Tothill House.

THOMAS ARCHER BEWES 1803 – 1889.

The Reverend Thomas Archer Bewes was born in 1803 and baptised at St. Andrew’s Church in Plymouth. His family, who had their own firm of solicitors, were originally from Cornwall and had lived at Beaumont House since the 1740’s. His father married Frances Culme in 1799 who was the daughter of John Culme, a neighbour and wealthy landowner who owned most of the land in the Tothill and Lipson areas. In 1825 Thomas had graduated from Exeter College in Oxford and became Deacon of Exeter Cathedral in 1826. He then went on to become Curate in the parish of Duloe near Liskeard in Cornwall, where his family had large interests in farming. He stayed there for about eight years after which he moved to Tolland, near Taunton in the county of Somerset. After residing there for about twenty years he moved back to Plymouth in 1856 and became the new Squire of Beaumont. He died in the summer of 1889.

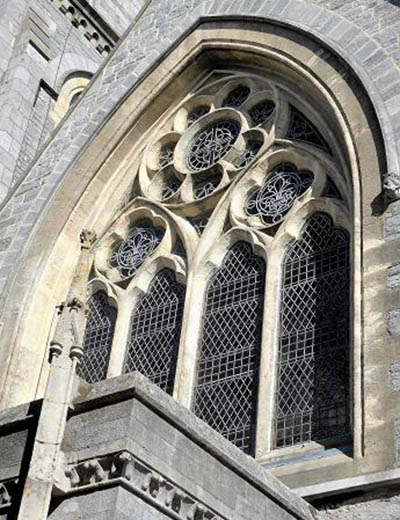

Since the building of Charles Church in the middle of the 1600’s, it wasn’t until almost 200 years later that any more churches were even contemplated in Plymouth. Then during the 1820’s two new churches were built, Charles Chapel and St. Andrew’s Chapel. In the 1840’s a further five churches were built, St. James, Christchurch, St. Peter’s, St. John and Trinity. It was in 1872, with Thomas Bewes as benefactor and the Culmes as landowners, to cater for the rapidly expanding population in the Eastern parts of the parish, that plans were beginning to take shape for St. Jude’s Church. The agreed site was a field called Higher Barn Park. The architect was James Hine of Plymouth and its architecture is classed as ‘Gothic Revival’ and was very popular throughout the 1900’s.

This wonderful style of architecture is defined by its vaulted roofs, buttresses, pointed arches, large windows and of course spires. It is also divided into different periods. Originally introduced from France ‘Early Gothic’ style architecture flourished in England from about 1180 up until around 1520.

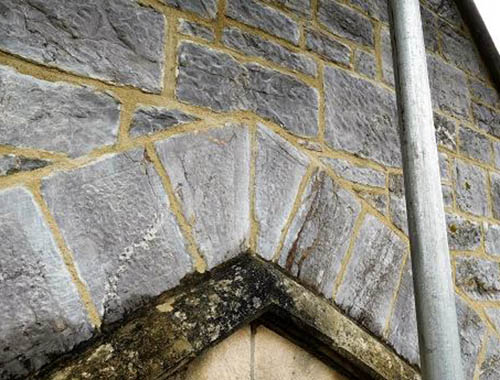

This Grade II listed church is built mainly from dressed Plymouth limestone, other stone was also used in its construction, red Balmoral granite from Scotland that was used for columns in the spire and doorways, the use of slate for louvres in the tower windows, Bathstone for detailing the tracery windows, Portland stone which was used in the label moulds, string courses and buttresses, a red Devon sandstone also for columns in the spire and Dartmoor granite which was used for steps and thresholds.

Other details include figures carved from Portland stone that are built into the ‘set-back’ buttresses, so called because they are set back from the corners of the building which they strengthen.

These little creatures are often mistaken as ‘Gargoyles’.

A ‘Gargolye’ is usually found much higher up at roof level and its purpose is to direct the rain water from the roof, out of its mouth and straight down to the ground.

As water doesn’t actually spout from the mouths of these guys they are technically called ‘Grotesques’.

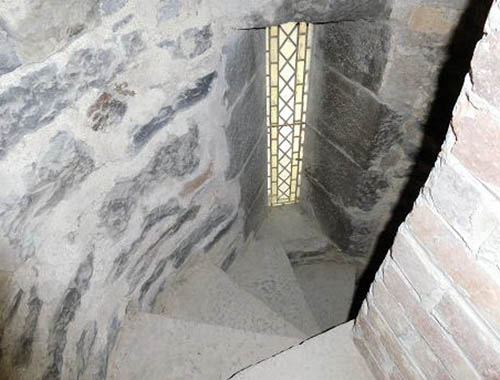

St Jude’s was built in 1875 and the main contractor appointed to carry out the work of constructing the new church was John Blatchford of Tavistock. He built the nave and chancel along with the North and South aisles and all built back then for the grand old sum of £3600. Once completed the church could accommodate around 650 people. Work on the tower and spire commenced in 1881 and by late 1882 that too was completed. Access up through the tower is gained by climbing up a narrow winding spiral staircase, the steps cut from Dartmoor granite.

And when you get to the top you are greeted by the church bell.

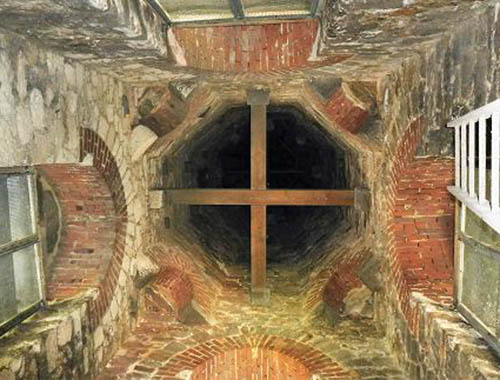

Along with the view of the internal construction of the spire high above you.

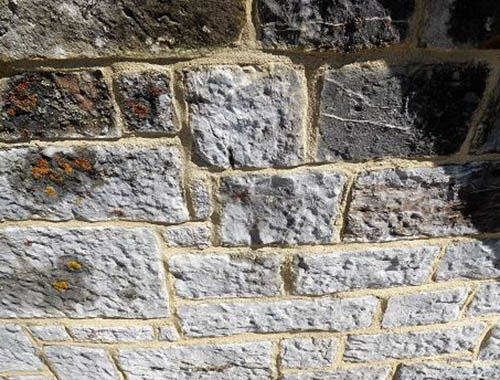

At some time during the late 1890’s the stonework to West wall elevation had re-pointing undertaken to try to remedy the problem of internal damp problems. As neat and tidy as this work had been done, cement mortar was used to carry out the re-pointing. The problem of damp still persisted to this day. The present church warden contacted us and asked if we were interested in pricing and carrying out the work. Once agreed a scaffold was put in place for us to gain access to the work.

The problem with using cement based mortar in stone buildings is that when it rains, penetrating moisture gets trapped within the stonework and can’t escape back out through the jointing. Moisture will then track back to the internal walls causing all sorts of problems. And judging by the expressions of these two chaps, no wonder they aren’t happy! They are also classed as ‘Grotesques’. These two are carved from Portland stone and rest at the foot of the ‘label’ mould either side of the window on the West elevation, probably depicting a couple of Saints.

A conservation architect had been appointed by the church who had set out a specification detailing the work to be carried out. This involved cutting out the old cement pointing in the stonework back to a depth twice the width of the joint itself. Once cleaned out and prepared it had to be re-pointed in a new lime based mortar which would allow moisture to escape in the future and the stonework to breathe. The new mortar consisted of using two and a quarter parts of course yellow ‘Zig-Zag’ sand from Newton Abbot, one part 3.5 N.H.L. lime and a very small amount of black grit. To make things easy for us to remember we used the ratio of 9:4:1/2 (sand/lime/grit).

Once all the jointing had been cut back to the required depth, the joints were flushed out with clean water using a low pressure spray to remove all traces of dust and debris.

After all the preparation work had been completed, we had to produce a sample panel for the approval of the conservation architect whereas the joints were dampened again and we proceeded to carry out the sample with the new lime mortar mix.

The specification asked for the new pointing to be ‘weather-struck’ which means that the mortar is slightly set back from the bottom edge of the stone at the top of the joint and the bottom of the joint covers the top edge of the stone below. This helps to shed the water away from the jointing. Once the architect had approved the sample panel we were good to carry on with the rest.

After the initial set of the mortar taking place it is then stippled with a stiff bristle churn brush. This helps to compact the mortar into the joint and removes any excess mortar on the stone. It also gives a neat finish to the jointing as it exposes the course aggregate within the mortar.

During the curing process the new jointing is sprayed several times a day with clean water to keep it damp so it does not dry out too quickly, this prevents cracking and shrinkage.

The coping stones that run down either side of the gable end had been made from Portland stone. Several of the joints had failed and the mortar specified for this was the same gauge as the pointing used for the stonework, only a N.H.L 5 lime was used instead which is slightly stronger.

After several days of curing this mortar dries out a pale cream in colour. It matches the colour of the original mortar used for the laying of the stone and after a few months of weathering it will tone down.

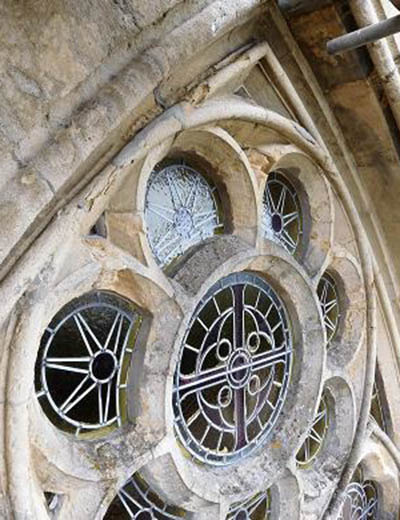

Whilst on site and to make good use of the scaffold, we were asked to take a look at the condition of the Bathstone which formed the tracery window on the West elevation wall. Despite repairs which had been carried out to this window in the past using a cement based mortar, generally, it was structurally sound and wasn’t in a bad state of repair.

However a few areas needed attention and as stone replacement was not an option at this stage these areas were to be addressed in the following ways. The conservation architect specified that the deep spalled areas were to be prepared, pins inserted if necessary and repaired with a lime based Bathstone mortar.

Other areas consisting of loose friable surfaces were to be carefully removed, brushed back to a sound substrate and then sealed with a stabilizing primer. The primer specified was ‘SecilTEK AD 25’ silicate primer. Silicate based primers and paints were initially developed for King Ludwig I of Bavaria in the 18th century for his castles. He wanted a paint that looked and performed as well as lime wash but was much more durable in the harsh winter climates. Examples of these paint systems still exist in Germany to this day more than a hundred years later. The primer we applied forms a chemical bond with the stone, it not only stabilizes the loose surfaces, it has high water resistant properties that does not alter the colour of the stone and more importantly as it is one of the most ‘breathable’ primers on the market, it allows the stone to breathe.

Existing loose cement based repairs were to be removed and repaired accordingly and any hairline cracks and fissures had to be primed and a small amount of the repair mortar pressed into the cracks to prevent water getting in and potentially freezing causing further damage in the future. Any failed and open joints within the tracery were to be re-pointed. A sample of the repair mortar was prepared for the architect to approve.

And a small amount of this mortar was placed onto a section of existing Bathstone for comparison and then left to cure.

Once approved we could carry on with the repairs.

And when the repair mortar cures, it blends in pretty well with the existing. We have also carried out work to the stonework and windows on the bell tower, and if you want to see what was done there, then all you need to do is to just click here.

The church itself has some fine examples of stained glass and here are a few of them.

And this one depicts the man himself, St. Jude, who incidentally is holding an effigy of St. Jude’s Church and is also the patron Saint of lost causes.

Once all the work had been completed the site was tidied up and the scaffold dismantled.

Much of the historical information about St. Jude’s Church contained within this web-page can be found in a little book published by the Parish Church of St. Jude’s.

It is called

‘The Master Builders’

and written by Clifford Trethewey.

There is an interesting poem mentioned in the book about the characters involved in the building of this church and it goes something like this…………..

“Whoever thought to build a Church

On such a lovely spot?

We’ve got St. John’s and that’s enough”

Said Mary Caldicott,

And the Jordans at the Round House

Could not believe it true,

Until they saw the hedge pulled down

And building stone in view.

Then came a sign announcing that

St. Jude’s Church would be there

Which made the Friary courting folks

Near topple with despair.

The builder was a portly man

John Blatchford was his name

And when he saw a chance in town

From Tavistock he came

His contracts were, apart from this,

Ham Chapel and North School;

Which later work he also did

Upon the Golden Rule,

His help was mostly country boys –

He brought a batch along –

And big Sam Slade, I well recall,

Was noted for his song:

This hairy man from Goose Fair town

Could sing for saving souls,

But when at work his only song

Was “Down among the coals”.

There was Windsor Jake a stonecutter,

With earrings in his ears,

Who used a mallet with a split,

Which had not worked for years:

No sooner did he rap the tool

When out an insect fell

And when he tried to crush the thing

They fell like peas – pell mell!

There was another mason man

Who crowed above the lot

Because he drank from out a pail

Instead of from a pot.

And Spider Rendle, when he chipped

The stone upon his banker,

Choked up his moustache ’till it looked

Much like a creamy anchor.

A Yankee stranger called one day

And with a blustering air

Called out to John Doidge, on the roof.

“Come down, or I’ll come there”

The foreman was a nice old man

And scanned his eyes to see

The man who could be so uncouth

To shout so loudily.

He, getting no word, then and there

Climbed up the ladder, bold,

And said “I haven’t seen you John

Since I was seven years old”.

There was a simple Joe, the hod-man,

Whose home was in South Shields,

Whose knowledge about building work

Was less than tilling fields;

For Charlie Doidge and Jimmy Doidge –

Two plasterers – did declare,

He carried bean poles fifteen miles

To save the railway fare!

There was a negro labourer

Who looked black to the bone,

The man was hired by Mr. Doidge

To help to saw the stone.

And for his unkempt impudence –

As he wore baggy pants –

We screwed a straight-edge in his seat

And weighed his balance.

He wrestled for a while, and then

We saw the sawyer dance;

He turned round like a Catherine wheel,

And freed himself by chance.

The negro’s chum, when half-way mad,

Would cut up like a fool;

He was a Labouring Union man.

His name was Harry Jewell.

He came in his Militia clothes

One day to go to work,

And, Mr. Blatchford, seeing this

Just drove him from the kirk.

Jack Protheroe, the carpenter,

He had a funny saw,

That buckled like a piece of tin

At every drive and draw,

Till the man from Thornhill’s Nursery,

Across the Northern aisle,

Brought John a string of onions

To strengthen it awhile.

The chimney caps are grinding stones –

Which brought a joke on me.

I used a rasp to smooth the hole

That it might clearer be.

And Squire Bewes enjoyed the jokes,

When’er he toddled round;

He little said, but thought a lot,

Within his Beaumont ground.

The sheds were by the Southern wall

The cook-house near a tree.

We worked an hour ’till eight o’clock

Then breakfasted on tea.

Some said the smell of broiling cod

Blew up from Anthony’s farm

Whilst others said “Tis Greenbank stew,

And that can do no harm”

I went to school in Shepherd’s Lane

And sung in St. John’s choir

And worked right through the edifice,

From footings to the spire

Yet, ‘ere I close I wish to say

There’s a lot of things untold

But this will furnish some idea

Of days we now call old.

For instance, inmate visitors

Attired in pauper garb

Would often call on Wednesday’s

And loiter in the yard.

They often got their “baccy” here

For telling us their woe

And now and then a penny too

Before they cared to go.

Oh yes, There were diggers and mechanics

There were men of many moods,

All earning bread and butter

At the building of St. Jude’s.

(A Tribute by someone unknown.)