Bedford Hotel, Phase One ~ Tavistock, Devon.

Client : Warm Welcome Hotels.

The ancient market town of Tavistock is named after the River Tavy which it is situated on and built around the Benedictine Abbey of St. Mary and St. Rumon that was founded here in around the year A.D. 974. It was destroyed twenty-three years later by the Vikings in A.D. 997, but by the year 1027 it had been re-built. And, in 1285 the abbey had been re-built again. By 1305 the area had become one of the richest sources of tin in Europe. Ruling the town more or less unchallenged for centuries, the secular Benedictine abbots had made Tavistock the richest abbey in the South-West of England which enabled the greater part of the abbey complex to be constructed during the 1450’s. The abbey was demolished in 1539 A.D. after the Dissolution of the Monasteries by order of King Henry VIII. The ruins of the abbey are still visible in the town centre today. Following the Dissolution, Tavistock and the surrounding lands fell into the grasp of the Russell family, who were Earls and later Dukes of Bedford. With the discovery of copper and arsenic in the area in the mid 19th century, Tavistock became a boom town, earning the 7th Duke of Bedford the tidy sum of more than £2 million alone, roughly equivalent to £250 million in today’s money. It was after all one of the biggest copper mining operations in the world. The Dukes of Bedford were responsible for many of the buildings we see in Tavistock providing housing and civic amenities for the mining community who lived in Tavistock and worked the extensive and lucrative copper and arsenic mines. As a consequence of its industrial history, in 2006 UNESCO designated the town of Tavistock as a world heritage site, it being the Eastern gateway for the ‘Cornish and Devon Mining Landscapes’.

In the heart of Tavistock town is the historic Bedford Hotel. It is situated amongst the remains of the old abbey precinct which is classified as a Scheduled Ancient Monument. In its three hundred year history there have been two hostelries within these grounds, the first one built in 1719, and the present Grade II listed hotel was built in 1822.

At the bottom of the car park of the present day hotel, is a small bridge that goes over a stream.

Cross that bridge and you’ll find yourself in the tranquil gardens of the hotel surrounded by the original Medieval wall of the abbey grounds.

The wall is fourteen feet high, built of local Hurdwick stone along with slate and granite crenellations along its parapet.

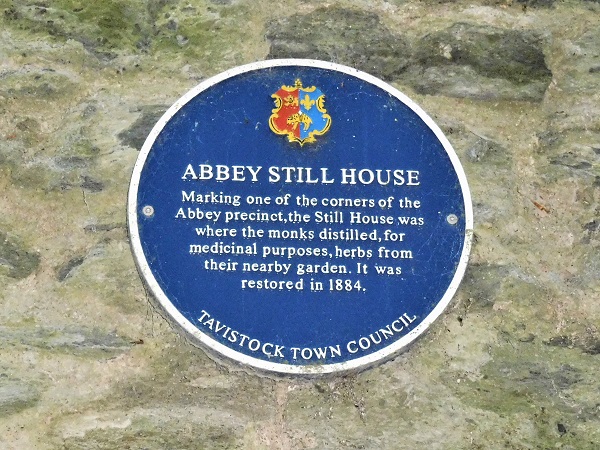

In the South-West corner of the garden is the ‘Still House’. This small Medieval tower is where the monks once distilled their herbs for medicinal purposes and probably formed part of the infirmary buildings within the abbey.

The ‘Still House’ is about twenty feet high and just like the abbey wall it’s built from Hurdwick stone, some slate and the top crenellated with granite. Original window features and arches make up its architecture.

Step onto the other side of the wall and you’ll find yourself walking alongside the river Tavy with Abbey bridge spanning the river and a series of weirs. There has always been a bridge here since Medieval times to serve the abbey. It was replaced in 1763 with a bridge consisting of two segmental arches cut from Dartmoor granite to accommodate the new turnpike road system that had been put in place at the time. Then, at the expense of the Duke of Bedford, it was widened in 1859/60 to cater for the ever increasing numbers of traffic from the nearby Great Western Railway station.

The hotel we see today is built over what was once the dining hall of the old abbey complex. In 1712 Jacob Saunders, a wealthy merchant, acquired the lease for the land and between then and the year 1720 he systematically set about demolishing what was left of the abbey chapter house, burial plots and other monastic remains in order to plunder the stone and build himself a lavish dwelling, upsetting many people in the process. Saunders never saw his dreams come to fruition, he died in 1725. His son John Cunningham Saunders took over and when he died in 1752 the Duke of Bedford bought the lease along with the house which was then used for accommodation by agents and stewards of the Duke’s Estate. It was known as the Abbey House up until 1822, and then changed to the Bedford Hotel when the present hotel was constructed. Saunder’s house now forms the East side of the Bedford Hotel with the hotel in part containing the stonework from the original abbey complex itself. The new Bedford Hotel was designed by Jeffry Wyatt who amongst other things was responsible for the transformation of Windsor Castle in 1824.

Look out the front entrance of the hotel and across the road and you are greeted by the ancient remains of the abbey cloisters.

The Bedford Hotel had contacted us initially as they were concerned when a small corner section of the string course at high level had fallen onto the pavement. Luckily no one was hurt. However, to get access for us to even inspect the string course required a substantial amount of scaffolding put up, so it was decided that whilst the scaffolding was up, it made sense to carry out any repairs and re-pointing at the same time.

Basically our instructions were to remove any loose and all cementitious pointing then re-point in a traditional lime mortar. Also, take out any cementitious plastic repairs back to the original underlying stone along with any repairs required to make the string courses safe.

Our first task was to remove a considerable amount of ivy vegetation which had taken root on the elevation from the ground level up to the parapet. This was now dead as the main root had been cut the previous year, but much of the root systems had found their way deep into many of the joints of the stonework. Some of them had even penetrated the soft Hurdwick stone causing the surfaces to spall away. The string course and stonework at the top along the parapet was mostly covered in moss, and this also had to be removed prior to any repairs were carried out.

Once all the vegetation and moss had been removed it was evident that most of the pointing to the stonework had been carried out using a cement based mortar in the past.

All the cement jointing was cut out, prepared and re-pointed using lime.

We proceeded to work our way down the building, cutting out joints and re-pointing as we went. The stone used in the construction of the hotel is Hurdwick stone and is sometimes called ‘Greenstone’ hence its colour. The volcanic stone is local and came from a quarry at Hurdwick which is just a few miles up the road and it has been extensively used in Tavistock and the surrounding areas since the Medieval times for the construction of countless prestigious buildings in and around the Tavistock area. It is very soft by nature and doesn’t weather very well and susceptible to frost damage and decay. The quarry is no longer working.

The lime mortar we used needed to be softer than the stone so we used a gauge consisting of five parts silver sand, one part yellow sand and two parts lime putty with the addition of ten percent pozzolan.

Using a pozzolan is beneficial when applying lime putty mortar in damp, frost prone or exposed locations. Adding pozzolan to lime mortars increases its compressive strength by offering additional protection during the carbonation period. Traditionally, volcanic ash, brick dust and other forms of burnt clay were used as additives in lime putty mortars. The term ‘pozzolan’ originates from the Italian town of Pozzuoli where the local volcanic ash was used to make the first effective form of concrete during Roman times. This made possible the construction of the cupola for the Pantheon in Rome, which is still the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome, and almost 2000 years old. We used ‘Argical M-100’ which is a modern refined form of pozzolan.

The string course was next on the list to sort out. Originally when Jacob Saunders had built his house, which is the East section of the hotel today, the string course had been detailed in Hurdwick stone. It had been re-modelled using a cement based mortar, and this was most probably done in 1822 when the hotel was built. Sections of the string course consisted of a patchwork of different repairs that had deteriorated and needed attention.

The string course was inspected thoroughly and anything deemed loose or unsafe was cut out and prepared for repairs. Most of the original material used to form the string course is what is known as ‘Roman cement’ which is misleading as it is a material that the Romans would certainly not of used. Roman cement was patented in 1796 and it is made by burning ‘septaria’ which are nodules found in certain clay deposits, and that contain both clay minerals and calcium carbonate. The burnt nodules were then ground into a fine powder. This product, when mixed with sand, will set in 5–15 minutes depending on the ratio used. There were many companies producing this type of cement at that time and they all varied to some degree until cement was standardized around 1845 and is now more commonly known as (O.P.C.) Ordinary Portland Cement.

Formwork was put into place to follow the existing profiles of the string course.

And being made from cement, the conservation officer agreed that we could use a cement based product to carry out the string repairs. We used ‘Renderoc H.B’. This is then applied in layers and gradually built up to follow the profiles.

Renderoc H.B. is supplied as a ready to use blend of dry powders which requires only the addition of clean water to produce a highly consistent, lightweight repair mortar. The material is based on Portland cement, graded aggregates, lightweight fillers and chemical additives which is polymer and fibre modified to provide a mortar while minimising water demand. The hardened product has excellent thermal compatibility with other stone and concrete substrates and has outstanding water repellent properties. On completion before the final set, the repairs are trowelled to a smooth finish.

And then the formwork is stripped away.

Plastic repairs were another issue we had to deal with. A plastic repair refers to a repair applied to stonework using a repair mortar, usually cementitious in composition, to eroded or damaged surfaces of the stonework to return it to its original profile. Most are coloured to match the surrounding masonry. These repairs are usually carried out as a low cost alternative of repairing masonry facades or individual units of masonry. In practice they can be unsightly and often carried out by low skilled labour with little attention to the quality of the finish and very little regard to the materials used, so long as the repair looks reasonable. Rather than performing any specific function these cementitious repairs often cause far more damage than good, and the hard cement surface will weather differently to natural stone. But these repairs have their advantages if carried out correctly using the right materials. Colour matching can be very difficult as stone is a natural material, no two pieces will ever be the same, and the mortar needs to be produced for the specific stone being repaired and not for the whole wall in general. Also a plastic repair should match a ‘cleanish’ section of the stone and not a dirty or polluted surface. It will tone down in time on its own accord. More importantly, the texture and finish of a repair is crucial to how it performs, dirt, pollution, and organic growth will not perform differently to the colour of the repair but act accordingly to the texture.

The conservation officer wanted all cementitious repairs removed, the stone surfaces stabilised to prevent further deterioration and then just re-pointed as they were. With Tavistock being a World Heritage site, no plastic repairs were to be approved, even if a lime based mortar was suggested. After cutting out the cement repairs, the original stone surfaces were then stabilised with ‘SecilTEK AD 25’ silicate primer. Silicate based primers and paints were initially developed for King Ludwig I of Bavaria in the 18th century for his castles. He wanted a paint that looked and performed as well as lime wash but was much more durable in the harsh winter climates. Examples of these paint systems still exist in Germany to this day more than a hundred years later. The primer we applied forms a chemical bond with the stone, it not only stabilizes the loose surfaces, it has high water resistant properties that does not alter the colour of the stone and more importantly as it is one of the most ‘breathable’ primers on the market, it allows the stone to breathe. This primer was also applied to the string course to help prevent future water penetration.

On completion of this first phase of work, there was more to come, the painters came in and painted the sash windows, the cast iron downpipes, and then the scaffold was taken down.