Replica Napoleon Commemorative Stone ~ Dartmoor Prison Museum.

Client : H.M.P. Dartmoor.

In 1805 Great Britain was at war with Napoleon and thousands of French prisoners were confined to prison ‘hulks’ or derelict ships. This was considered to be unsafe as they were too close to Plymouth Dock (Plymouth Naval Dockyard) not to mention the appallingly harsh living conditions encountered upon these prison ships. A prisoner of war depot was planned for and this was agreed to be built in the remote isolation of Dartmoor.

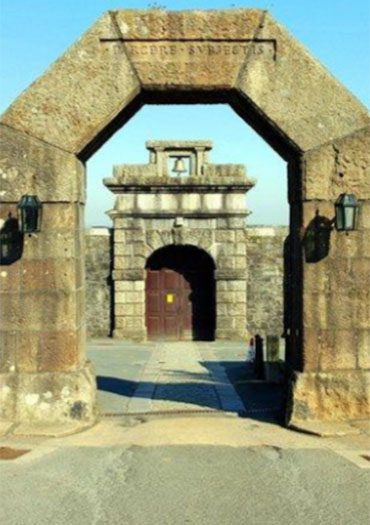

With its imposing entrance H.M. Dartmoor prison is located in Princetown high up on the western edges of Dartmoor. It was designed by British architect and engineer Daniel Asher Alexander and built within a three year time span between 1806 and 1809 by local labour. The initial cost of £130,000 was far exceeded and the contractor went broke. Originally known by the name ‘Dartmoor Depot’, it was designed to hold around 5,000 men. Later, because of overcrowding, two more prison blocks were built and the number of prisoners then rose to around 8,000. The land where the proposed prison was going to be built was owned by the Prince of Wales. Local landowner Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt the founder of Princetown was a close friend and secretary to the Prince and together they realised they could profit from the construction of the prison, the Prince by being paid a rent from the leasehold of his land and Tyrwhitt would supply the granite from his quarries for its construction. The first French prisoners arrived here during May 1809. The prison is one of the oldest prisons in Great Britain that continues to house prisoners to this day and is still owned by the present Prince of Wales and forms part of the Duchy Estates. The Latin inscription ‘PARCERE SVBJECTIS’ which is cut into the granite of the arched entrance translates as…..

‘Spare The Vanquished’

Back in 2015, we were approached by Alain Sibiril, the Honorary Consul for France based in Plymouth. Two hundred years earlier, Napoleon had surrendered to the British and whilst he awaited his fate he was kept for ten days on board the British naval ship the ‘Bellerophon’ in Plymouth Sound. We were asked to make a commemorative stone to mark that event and it is now located on Plymouth Hoe. The stone in question was prepared at Dartmoor Prison and the stone was donated by the ‘Duchy Estates’. Dartmoor Prison has its own museum, and because of the interest surrounding the Napoleon stone, along with the prison’s history with French prisoners during the Napoleonic wars, Governor Mrs. B. Oakes-Richards of Dartmoor Prison asked us if we could make a smaller replica of the original to be displayed in the museum there.

The original stone on Plymouth Hoe consisted of two pieces of granite, the base and an upright stone which represented the sail of a ship. The base stone was silver-grey in colour, whilst the ‘sail’ stone was pink. The hardest thing to do was to actually source two new pieces of granite that was going to be the same shape and colour. Also the two pieces needed to look natural and not look as if it was dressed, so they needed the minimum amount of work doing to them.

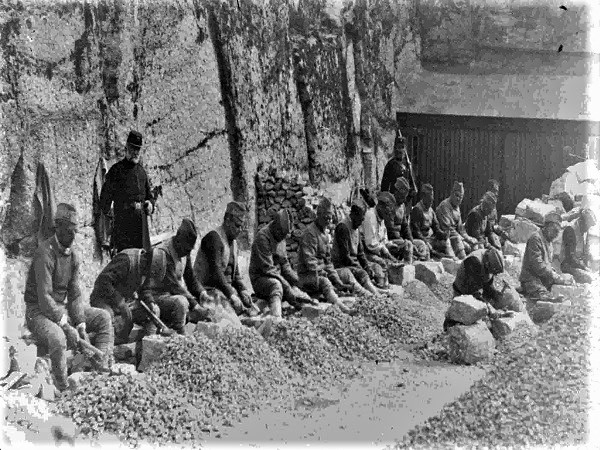

We looked in three locations on Dartmoor where stockpiles of granite are stored, and all locations are owned by the Duchy Estates. These areas proved to be fruitless and no suitable stone was found. There is a quarry just up the road from the museum, it’s called ‘Herne Hole’, this used to be the prison quarry where convicts carried out their hard labour. Here they crushed up granite all day long with hammers to make aggregate. It also supplied stone for some of the construction of the prison itself. It was originally owned by Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt.

Both of the above photographs (Courtesy Trevor James / Dartmoor Museum.)

Although a working quarry up until the 1980’s, the quarry is no longer worked today and is also owned by the Duchy Estates. There is no public access to this quarry and the Duchy Estates granted permission for us to look for suitable stone here.

Some old buildings still survive at the entrance to the quarry along with a tunnel that had been constructed under the road for the prisoners journey back to their cells.

Now completely overgrown and surrounded by the imposing working faces of the quarry, there was a substantial pile of granite that lay in the middle of the quarry floor.

Scattered around the quarry can be found various bits of finished granite that were once destined for other jobs, but never made it.

These included a huge granite pier cap.

A number of double chamfered-edge copings.

And this unusual bespoke piece, its purpose unknown.

Having spent a couple of hours looking around the quarry, two bits of granite were eventually selected that proved suitable for the new replica stone. Silver-grey for the base and pink for the ‘sail’ stone.

These were taken back to the Dartmoor Prison Museum. The buildings where the museum is housed today were once the prison dairy and consisted of a group of old buildings with an enclosed courtyard at the rear. It was in a corner of the courtyard where the new replica stone was going to be made.

The replica was going to be about one third of the size of the original stone on Plymouth Hoe.

The only work we had to do to the base stone was to ‘square-up’ the back edge. This edge was cut and then dressed back using a tungsten punch. Once set up in the museum, not much of this back edge would be seen.

The next part was to shape the ‘sail’ stone. To do this, first we drill in a series of holes along the line of where we want the stone to break.

Then iron wedges called ‘Plugs and Feathers’ are inserted into the drill holes.

Known by various names such as ‘Wedges and Shims’, here on Dartmoor these iron wedges are called ‘Feathers and Tares’. They are used to shape stone into rough dimensional units and also to extract stone from quarry faces. First mentioned in the United States in The New-England Farmer; Or, Georgical Dictionary by Samuel Deane in 1790, the technique was so efficient that within a year the price of quarried stone was cut in half. This technique spread quickly and is still used to this day, it has been used on Dartmoor since the very early 1800’s. The length of the ‘Feather and Tare’ will dictate the depth of stone you can split or extract. As a general rule of thumb you can split stone up to 4 to 6 times the length of the tare. This method of splitting stone replaced the ‘Wedge and Groove’ method, a technique requiring the stonecutter to cut a series of rectangular slots along the cut line approximately six inches long, three inches deep and about one inch wide. Wooden wedges soaked in water were then hammered into the grooves. Overtime, as the wet wedges expanded simultaneously, they forced the stone apart, and this was a time consuming operation as some stones could take up to twenty-four hours or more to split. The ‘Wedge and Groove’ method was used extensively throughout the Medieval period although there is evidence that the Egyptians used a similar method of splitting stone using bronze wedges instead of wood.

Once inserted into the holes the ‘Feathers and Tares’ are tapped in succession with a hammer. When they take hold, they make a ringing sound, and the force these simple tools produce split the stone across the line of the drill holes. This method was chosen as opposed to cutting it with a diamond disc cutter as it creates a natural break and the only tidying up required is to dress back the drill holes. A disc cutter would create a flat surface, and even dressing it back, it would look too smooth and clinical.

Two reproduction bronze plaques were faithfully reproduced by Photocast based in Liverpool. They had originally produced the two bronze plaques for the stone on Plymouth Hoe. These two new plaques were scaled down to about one third of the original size.

Here’s Trevor James with the two plaques.

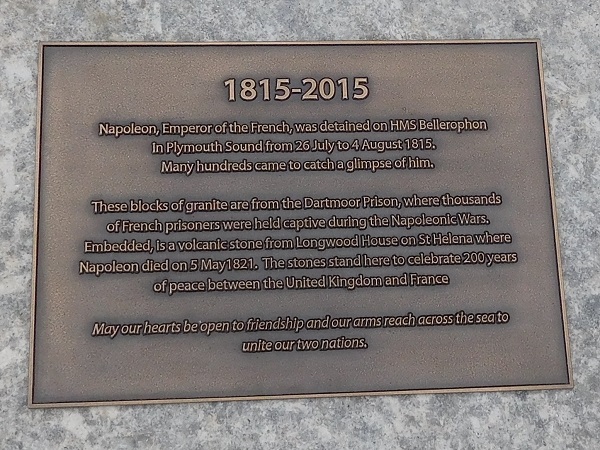

The wording on the plaque for the upright ‘sail’ stone.

And the wording on the base stone plaque.

The larger of the two plaques was going to be fixed to the base stone, and the corresponding drill holes were made to line up with the fixing dowels on the back of the plaque.

The smaller plaque was going to be fixed to the upright ‘sail’ stone. The surface was dressed back flat, and again the corresponding fixing holes were drilled.

The stone on Plymouth Hoe has a piece of stone from ‘Longwood House’ embedded into it. Longwood House is on the Island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, and it’s where the British exiled Napoleon after spending ten days in Plymouth Sound on board the Bellerophon. The replica was to have a piece also embedded like the original, and this was shaped and set into the top of the ‘sail’ stone.

Once all this was completed the whole thing was put together ‘dry’ to see how it would all look before being set up permanently in the museum.

In the meantime a wooden display base had been constructed and placed in a prominent position in the museum.

All the sections were brought into the museum and fixed together on the new wooden base.

Brian Dingle, present curator of Dartmoor Prison Museum.

From left to right. The Governor, Mrs. B. Oakes-Richards, Honorary Consul of France in Plymouth, Mr. Alain Sibiril and local historian Mr. Trevor James.

The base was covered in ‘astro turf’ on completion.

Above is the original stone on Plymouth Hoe. If you want to read about this project, you will find it here.